Article by Douglas Shedden, Technical Director, Medical Wire & Equipment Co.

In these days of centralised medical facilities, the patient is often far removed from the laboratory. In many cases they won’t even know where the laboratory is. But the link between the patient and the investigator is the patient’s specimen, which in many cases arrives on a transport swab. There is inevitably a transit period, and often a waiting period before processing if specimens arrive in large numbers. A swab specimen is not an inanimate object, instead it can be a site of intense biological activity and competition. If the specimen has been correctly collected, there will be some of the pathogenic bacteria which are the true aetiological agents, but there will inevitably be other factors present as well. These will include commensal bacteria from the surrounding tissue. There may be traces of topical antiseptics and antibiotics, and other interfering substances. The pathogenic bacteria are often in a fragile condition having been subjected to antiseptic solutions, as well as the patient’s own immune system. Given these challenges, it is essential that the transport device does not interfere with the specimen during transport or processing.

Bioburden – bacteria from the patient or from the swab? Gram stains are still regularly used as the first check on a specimen, for example during surgery. It is possible to identify presumptively some broad categories of microorganisms and in critical situations to commence treatment to eliminate danger. In such situations it is essential to know that the bacteria which are being seen are genuinely from the patient, and not already present on the swab. All transport swabs with semi-solid medium (and even some with liquid medium) contain agar, which is derived from seaweed and as such may carry a certain amount of bacteria. The swab device may have been sterilised by irradiation, so the bacteria are dead, but they still appear on Gram films and stain in the same way as live bacteria and can either be mistaken as the cause of illness, or simply make any kind of assessment impossible. In critical situations this can result in emergency administration of strong antibiotics, and cancellations of clinical procedures, including surgery.

A more recent phenomenon is that non-viable bacteria, or their remains, can be a source of antigens and DNA which can interfere with molecular testing systems, including PCR. Swabs which are manufactured in accordance with CLSI M40-A2 should have bioburden below specified maximum levels, but sadly this is not always the case. Responsible users must request detailed confirmation of compliance from their supplier.

What you should see:

Gram films from Amies medium plain and charcoal

What you might see with non-compliant swabs:

Gram films from Amies medium plain and charcoal

Overgrowth – true pathogens or opportunistic commensals? When collecting a specimen with a swab, other bacteria may be present at the sampling site, and are picked up in addition to the pathogenic strains. While the pathogens may be in poor condition from attacks by the immune system, and are often fastidious, these other bacteria are well adapted to rapid growth even with limited nutrients. The result is that these commensals do grow rapidly, overwhelming the fragile pathogens which will tend to die off and be undetectable. In such circumstances the laboratory will be unable to detect and identify the pathogens, and so the patient can not be provided with appropriate treatment.

Recovery of key pathogens Given the difficulties already described, it is essential that the transport medium used with the swab is capable of recovering the main types of pathogenic bacteria without interference from non-viable organisms or overgrowth from commensals. CLSI M40-A2 specifies a set of bacteria representing the typical spread of organisms seen by most laboratories. It requires these to be satisfactorily recovered, at ambient and refrigeration temperatures for a period of 48 hours, to represent the range of transport times and conditions which could be used in most laboratories. The exception is Neisseria gonorrhoeae for which recovery is only tested at 24 hours. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is included at refrigeration temperature (4oC) as a test for overgrowth.

To be compliant with CLSI M40-A2, manufacturers are required to test the specified strains for these organisms for recovery using both an elution method and a roll plate method. Users should also perform the tests, but can choose one of the methods.

The organisms which have to be tested in an M40-A2 programme are all of: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC®BAA-427 Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC® 19615™ Haemophilus influenzae ATCC® 10211™ Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC® 6305™ Bacteroides fragilis ATCC® 25285™ Peptostreptococcus anaerobius ATCC® 27337™ Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC® 25586™ Prevotella melaninogenica ATCC® 25845™ Propionibacterium acnes ATCC® 6915™ Neisseria gonorrhoeae ATCC® 43069™

Which would you choose?

Recovery of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from different transport swabs after 24 hours at 40oC

Recovery of Streptococcus pneumoniae from different transport swabs after 48 hours at 21oC

Recovery of Streptococcus pneumoniae from different transport swabs after 48 hours at 21oC

Gel or Liquid? For many years most laboratories and authorities have used gel transport swabs, normally with a plain or charcoal version of Amies medium. When properly prepared and controlled, this is particularly suitable for anaerobes and fastidious organisms because the viscosity of the semi-solid medium slows down the diffusion of air (oxygen) which many of these organisms find to be toxic. Care should be taken in selection of a suitable medium because these can have a high level of bioburden (non-viable bacteria) which can interfere with Grams stains and molecular testing.

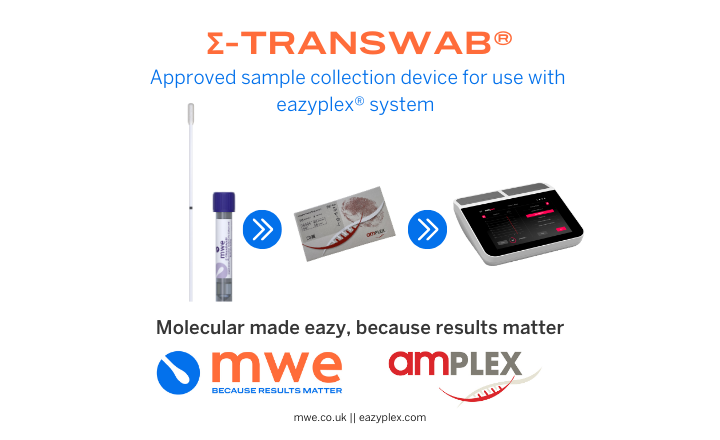

Recently, with the advent of automated plating systems, swabs with liquid Amies have been introduced. Liquid medium has the advantage that the specimen becomes uniformly dispersed, and can then be readily used for multiple tests, unlike the gel which requires some processing to remove the collected bacteria from the swab bud and the gel medium. It is still important that the swab device with liquid medium is fully compliant with CLSI M40-A2. This presents a significant challenge to the manufacturers, but in devices such as Sigma Transwab® with Liquid Amies from MWE, that challenge is fully met, and the performance is just as good as Transwab® with Amies Gel (Plain or Charcoal).

With liquid systems a variety of special media are also available, such as liquid Cary Blair for enteric specimens, Lim Broth for Streptococcus agalactiae, and Tryptic Soy Broth with Sodium Chloride for Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA.

Swab Tips? The earliest swabs had cotton buds on wood or wire shafts. With the advent of transport media such as Stuart’s in the 1940’s it was quickly discovered that cotton was not at all suitable for this function. Cotton fibre is a natural material that contains fatty acids with anti-bacterial properties. It is very unsuitable for recovery of fastidious bacteria. Calcium alginate fibre had a period of popularity because of its solubility in certain liquids, allowing greater release and recovery of the collected organisms. It has been shown, however, to interfere with molecular test methods. It still has its uses in more general fields of microbiology, but it can no longer recommended for clinical specimens.

Spun rayon fibre is now the material of choice for gel transport swabs. It does not cause interference with recovery. It is important, however, to use swabs with buds which are not too tightly wound or bacteria become trapped and are not released into the medium.

With liquid media some novel formats have become available and are better suited. Open celled soft foam, and flocked polyester or nylon fibre tips allow good pick up of specimens and good release into the liquid medium, so that the liquid becomes the specimen in the true sense of the word, and is readily processible, whether on automated platforms or by conventional methods.

Automation – Unexpected Item in the Processing Area! The development of large centralised laboratories, often running 24 hours 7 days each week, and especially with the requirement for large scale screening for healthcare associated microorganisms such as MRSA, has led to many such laboratories acquiring automated processing platforms. Most of these are designed to work with liquid specimens. The i2a Prelud can work with liquid or gel. While some of the machine manufacturers will encourage use of their own swabs, it important that the equipment chosen can be used with whatever swabs are submitted by users and these can vary because of regional overlap for many disciplines. Most manufacturers recognise this and provide guidance for the type of swabs which can be used.

For swab users it is important to purchase M40-A2 compliant liquid swabs which are compatible with the equipment. For example, MWE Sigma Transwabs are compatible with all current systems including Alifax Sidecar, Beckman AutoPlak, BD Kiestra TLA, i2a Prelud, and Biomerieux/Copan WASP®.

Molecular systems The rapid development of PCR based technology has led to many molecular platforms which are able to rapidly and accurately detect and identify infectious organisms including viruses, bacteria, yeasts and fungi, faecal parasites, mycobacteria including tuberculosis, chlamydia, and mycoplasmas. ELISA and lateral flow-based tests are also widely used. For any of these the transport swab is still the main specimen type, so it is essential that the medium and swab are not inhibitory in any way to these tests. If a particular swab or other device has not been validated by the system manufacturer it may be necessary to conduct an in house validation following guidance such as that provided by ASM’s Cumitech 31A.

ISO 15189 Accredited laboratories are responsible for ensuring that the consumables they use are properly validated and capable of giving accurate results for all the diagnostic tests they are used for. In this context transport swabs are not just another consumable or commodity. They are the interface between the patient and the laboratory, and essential medical devices that can affect the quality of diagnostic reporting, and the service provided to the patient. A laboratory can have all the latest and most expensive technology, but if the microorganisms have died off on the swab, or if the swab has high numbers of dead bacteria from seaweed, any tests are going to be compromised and likely to fail.

Be sure the swabs you use are not the weak link preventing you providing your patients with the service they expect and deserve.

"Nothing is more important to the effectiveness of a laboratory than a specimen that has been appropriately selected, collected and transported. If specimen collection and management are not priorities, then the laboratory can contribute little or nothing to patient care or related investigations." - J. Michael Miller in “A Guide to Specimen Management in Clinical Microbiology” ASM Press, 1996

References 1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Quality Control of Microbiological Transport Systems; Approved Standard—Second Edition CLSI document M40-A2. Wayne,PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2014 www.clsi.org 2. Clark, R.B., M.A. Lewinski, M.J. Loeffelholz, R.J. Tibbets, 2009, Cumitech 31A, Verification and Validation of Procedures in the Clinical Laboratory, Coordinating Editor S.E.Sharp, ASM Press, Washington DC. 3. ISO 15189:2012 Medical laboratories — Requirements for quality and competence. International Standards Organisation, 2012, www.iso.org